As a preclinical researcher working in a lab environment, my day-to-day work focuses on developing new treatments, diagnostics, and vaccines for tuberculosis (TB). However, I recently had the opportunity to participate in a site visit during the 7th Global Forum on TB Vaccines in Rio De Janeiro, which gave me a glimpse into the clinical side of public health relating to TB.

I believe it’s essential for preclinical researchers like myself to be exposed to the clinical side of TB care and prevention. After all, we are developing new tools that will eventually be used in the “real world”. It’s crucial for us to understand the requirements of the healthcare system and local communities, as well as engage with them about potential new vaccines and delivery systems.

The site visit took me to three different locations: a Family Health Centre, a Surveillance Centre, and a Vaccination Centre. Each location provided valuable insights into the clinical side of TB care and prevention in Rio De Janeiro.

Family Health Centre

The first site I visited was the Clínica da Família Estácio de Sá in Rio De Janeiro. What struck me was the clinic’s impressive 90% treatment success rate, significantly higher than the national average of around 70%. The main reason for this success is the clinic’s ability to track patients and ensure they complete their treatment. Patients are registered at the front desk according to their community, and health agents from the same community deliver TB drugs on weekdays.

The clinic uses a range of diagnostic tools, including X-ray, TST, sputum smear, and culture. I was impressed by the clinic’s infrastructure and the health agents’ deep understanding of the local community’s needs. The fact that multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is relatively uncommon in Brazil may be due to the national health system’s control over first-line TB drugs. You can’t buy TB drugs over the counter in Brazil, so everyone, even if they’re millionaires, collect their TB medication from the clinic.

Surveillance Centre

The second site I visited was at the Centro De Operaçoes Rio Prefeitura, a centralised monitoring system for outbreaks and disease surveillance. The centre’s implementation is designed to minimise additional friction on busy healthcare workers, allowing them to focus on patient care. The data is grouped by municipality, and healthcare centres and government agencies can access it.

I was impressed by the centre’s ability to predict outbreaks up to four weeks in advance, using data on temperature, humidity, and other factors. The centre also monitors traffic, temperature, and power distribution, providing a comprehensive view of the city’s public health situation.

Vaccination Centre

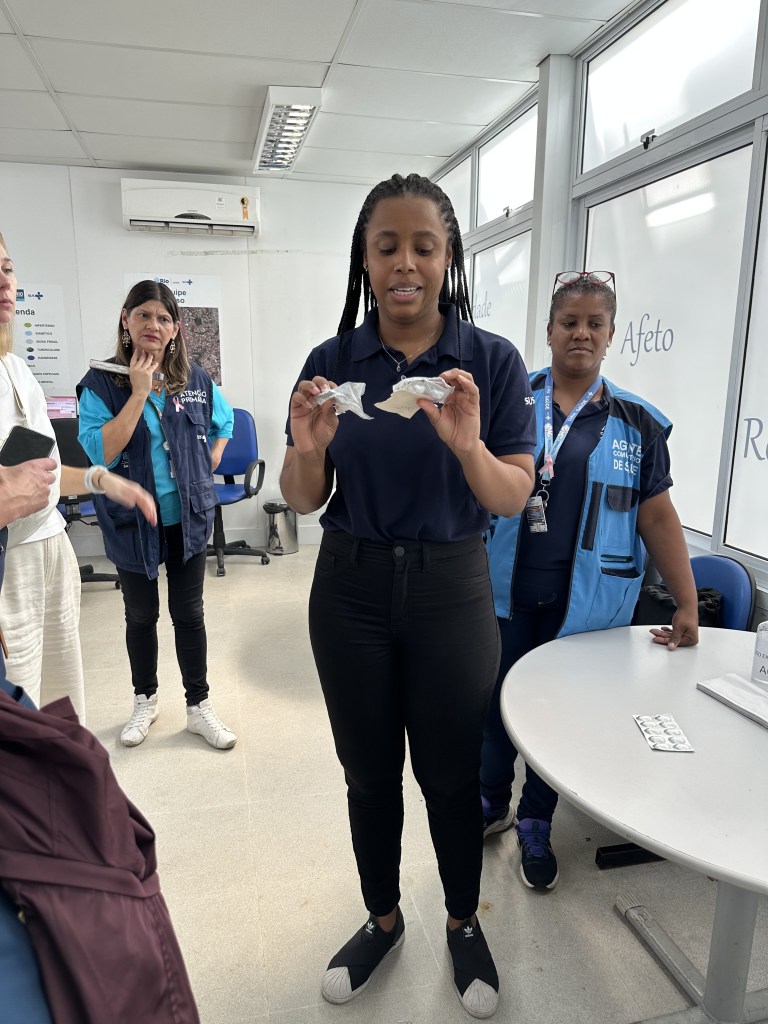

The final site I visited was a Vaccination Centre in CMS Rocha Maia, Rio De Janeiro. This centre serves the local community, offering vaccinations from 8am to 10pm, allowing people to visit after work or school. The centre has an outreach program that delivers vaccines directly to those who cannot attend the centre.

I was heartened by the low levels of vaccine hesitancy in the area and the enthusiasm for vaccination among people living in favelas. The centre’s use of a SUS mascot, Zé Gotinha, a character modelled after the “drop” of polio vaccine, has become a beloved symbol of vaccination in Brazil. Who says vaccines can’t be fun?

My site visit to Rio De Janeiro was an eye-opening experience that highlighted the importance of understanding the clinical side of TB care and prevention. As preclinical researchers, we must engage with local communities and healthcare systems to ensure our work is relevant and effective. I left Rio De Janeiro inspired by the dedication of healthcare workers and the commitment of local communities to public health.